Myanmar’s largest annual holiday, the Thingyan New Year Festival, is now a memory. Unlike last year, there were no merry celebrations with water cannons and crowds. Residents huddled away indoors to avoid COVID-19, the virus from Wuhan, China, which has caused a global pandemic.

So far, Myanmar’s case numbers are far lower than most nearby countries. Myanmar’s defacto leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has been using her Facebook account to say to her people ‘I wish that every individual citizen follows his or her duty responsibly to reduce the spread of the virus.’

But it would be a mistake for Myanmar to think that the only threat coming from China is COVID-19. For while Myanmar continues to focus on battling the virus, there is speculation on what Chinese President Xi Jinping is hoping to gain from Myanmar.

Xi’s Silk Road

China’s ambitions for Myanmar are clear – China sees Myanmar as an important link in its ‘String of Pearls’ approach to expanding its influence into South East Asia. Government officials and China experts across the world have explained how China is building a new Silk Road via the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as leverage over neighbouring countries, a means to project its influence and facilitate its infrastructure and military expansion.

China’s antics in the South China Sea exemplify its aggressive approach and bullying of neighbouring countries to comply with Xi’s vision of expanded Chinese maritime borders and outposted Chinese naval bases. Back in April, Vietnam’s foreign ministry made an official complaint to China over a Vietnamese fishing boat they claimed was rammed and sunk by a Chinese Coast vessel.

Experts identified the Kyauk Phyu Port in Rakhine State as China’s objective for direct access to the Indian Ocean, bypassing the contested Malacca Straits, and a logical choice for a Chinese military base – should China persuade Myanmar to agree to this use.

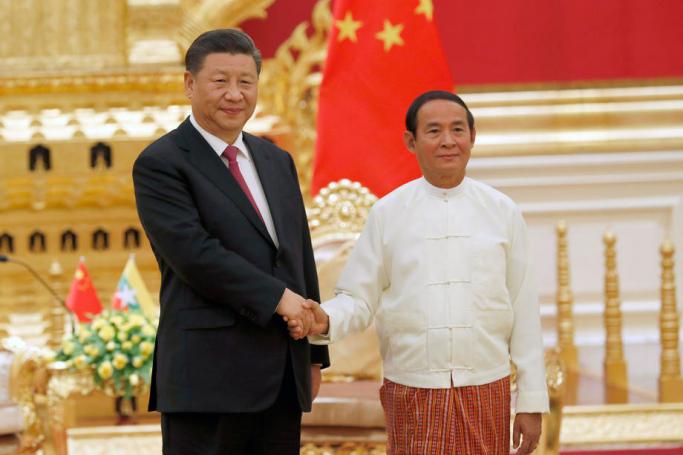

President Xi’s visit to Myanmar in mid-January – as the virus was beginning to claim lives in Wuhan – emphasized the importance of the US $1.3 billion Kyauk Phyu Port development and the associated economic corridor connecting it to China’s southern Yunnan Province.

Is China looking for more than a communications and trade corridor?

A Chinese military base is unlikely given the Myanmar government’s stance and the 2008 Myanmar Constitution, which forbids the presence of ‘foreign troops’. This provides the Myanmar Government with a convenient justification to deny any Chinese troops to undertake activities within Myanmar’s borders should such an approach be made.

Chinese Outreach

In January and February of this year, the world watched in horrified fascination as the virus exploded in China’s Wuhan, claiming thousands of lives and kicking off a global pandemic. Two months later, however, President Xi transformed China into the self-proclaimed ‘global leader on Coronavirus’ and turned up the tempo on its foreign relations to help other countries deal with the virus.

Since March 2020, China has sent masks, medical equipment and even some doctors to countries in Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia which have been hard hit by Coronavirus. The coordinated effort by the Chinese Government to create positive perceptions about China’s work on Coronavirus demonstrates that Xi is using the virus as a tool for its foreign policy objectives. Although some countries have praised the assistance in their time of need, there has also been criticism that masks and medical equipment have been of poor quality.

The approach that Xi decides on to advance China’s long term strategic ambitions in Myanmar could be linked to how the COVID-19 threat plays out in Myanmar.

The Monsoon Arrives

It is a strange holiday period for school and university students. Classes were supposed to go back in June, when the monsoon season began. Yangon’s hot dusty streets are now flushed out with torrential rain. However, all eyes are on Myanmar in how it handles the other storm.

Now that the world has witnessed the awful scale of deaths from COVID-19 in China, the US and Europe, there remains uncertainty over how things will pan out in Myanmar.

In April 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) told the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) that the crowded living conditions in ASEAN cities, weak contact tracing, and poor access to sanitation and healthcare facilities, means COVID-19 will impact ASEAN countries to a greater extent than in Europe and North America, unless they follow the WHO’s recommendations.

Back then there were concerns raised about how Myanmar might handle the pandemic. Myanmar did not have the funds at its disposal to follow the WHO’s advice – Myanmar’s GDP per person of US $1,325 is far less than Thailand’s US $7,200 or Singapore’s US $64,500. Additionally, with less than on hospital bed per 1,000 people, there were concerns back then that most of Myanmar’s COVID-19 patients could be left on hospital floors or untreated at home.

Today, we are seeing how the Myanmar authorities have handled the virus with just over 300 cases and only six deaths. State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has led the pushback, calling on people to be vigilant, and taking a “middle way” approach to tackling the virus with lockdowns, masks and sanitary methods that have kept the virus at bay. She has been helped by the comprehensive approach used by the Ministry of Health and Sports to keep a lid on the situation.

However, the impact of the virus containment measures goes beyond deaths to include: job losses, crime and occasionally protests. Ordinary Myanmar people lost jobs due to the sharp economic downturn – some of these newly unemployed with fall into poverty and turning to criminal activity. The UN World Food Program recently warned that the pandemic will trigger a massive famine in countries with poor access to nutrition. Reporting surfaced that drug cartels operating in the Golden Triangle and northern Myanmar are trying to take advantage of the chaos caused by the Coronavirus to up their narcotics shipments. Other South East Asian countries – Thailand, Cambodia, the Philippines and Indonesia – declared States of Emergency in order to give special powers to security services.

While Myanmar people are more resilient and used to hardship than Europeans and Americans, everyone has a breaking point and the authorities have to be sensitive to the challenges of trying to control the ethnic areas, prone to conflict, particularly in an election year.

Plenty of Options

We see three plausible avenues for Xi to take advantage of this situation.

Firstly, there is a possibility that China will seek to become more engaged in Myanmar’s ethnic areas.

Secondly, President Xi reportedly made a telephone call recently to Myanmar President U Win Myint to remind Myanmar about the raft of infrastructure and communications projects, many of which are lined up for a band of territory that stretches from Yunnan, China border to the Indian Ocean. He reportedly called to fast-track the projects.

Thirdly, China might use its might and influence to seek to clamp down on the flourishing narcotics trade in the Golden Triangle region, particularly when it comes to vital precursor chemicals sourced in China that are needed for the production of some illegal narcotics.

Myanmar-China Relations

It has clear that the coronavirus crisis has put Myanmar at a disadvantage vis-à-vis relations with its northern neighbour.

What the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us is to expect the unexpected. We must hope, however, that State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Senior General Min Aung Hlaing keep their eyes open to the long term risks, not just the opportunities, when China comes knocking to ‘help’ with COVID-19.

This anonymously-written opinion of an outside author does not necessarily reflect the views of Mizzima.