With easy access to Myanmar and remote Andaman Sea islands, the isolated coastal district of Khura Buri is a smuggler’s paradise.

The northernmost point of Phangnga province, it is an area steeped in natural wonder yet remains far from the prying eyes of tourists. Locals there live simply, their livelihoods dependent largely on the ocean and its abundant seafood stocks.

But for the gangs who operate there, the waters carry a far more lucrative cargo: humans.

Spectrum visited Khura Buri three times over the past two years, each time finding traces of human trafficking in the area.

About an hour by boat from mainland Khura Buri lies the large but sparsely populated island of Phra Thong, which has risen to notoriety in recent years as a transit point for Rohingya migrants being smuggled out of Myanmar.

Many Rohingya landed their boats on the island and burned them to prevent Thai authorities from pushing them back out to sea.

But it is not only Rohingya migrants who are using the district as a transit point as they move between countries.

Khura Buri was back in the headlines again recently with the revelation that Erawan bombing suspect Wanna Suansan had been living there with her husband, a Turkish national who is also wanted by police for his alleged ties to the human trafficking trade.

The coastal district is just a small part of the major transit centre for human smugglers that Thailand has become, with well-established trafficking routes now being utilised by other groups of migrants including Syrians and Uighurs.

“It is easy to come here, and you can find fake passports in Thailand,” said one official, speaking on condition of anonymity.

"The international smuggling rings have been operating here for years."

CENTRE OF ATTENTION

While the smuggling of Rohingya migrants has long been a lucrative business in Thailand, Uighurs fleeing China have been seized upon as a new opportunity by established trafficking gangs.

Until recently the practice has remained mostly under the radar, despite widespread international news coverage of human trafficking operations after the discovery of mass Rohingya graves in the South in May.

Surapong Kongchantuk, a human rights expert from the Lawyers Council of Thailand, said he has had no access to Uighur migrants, unlike Rohingya or Syrian groups.

But the lawyer, who has been actively working with ethnic minorities, stateless people, migrant workers and displaced persons, said he had begun to uncover some of the details of the smugglers’ operations.

“The reason that traffickers and smugglers choose Thailand as the transit point for all these refugees is because they are aware how easy it is to get people through our country,” Mr Surapong explained.

“Due to the location of our country, loopholes in our legal system and rampant corruption, Thailand is the perfect transit point.”

Mr Surapong said his team had discovered many of the smugglers bringing Uighurs through Thailand were part of the same networks that had been trafficking Rohingya, and even used many of the same trafficking routes.

He explained the traffickers saw Uighurs as a new and lucrative business opportunity since they generally are carrying a lot more money than Rohingya people.

PRICE OF FREEDOM

“When the Rohingya migrate from Myanmar, they have only enough money to pay the traffickers. The main purpose of their journey is to find a place to work and send home some money,” Mr Surapong said.

“However, the Uighur refugees have a lot more money since they generally sell everything they own back in China to migrate to their desired third country, which is Turkey. Therefore their spending power is much more than Rohingya group.”

Mr Surapong said his investigation had found that each Uighur migrant usually pays more than 100,000 baht for the journey from China to Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia. By comparison, Rohingya would pay 30,000 to 50,000 baht to get to their preferred destination.

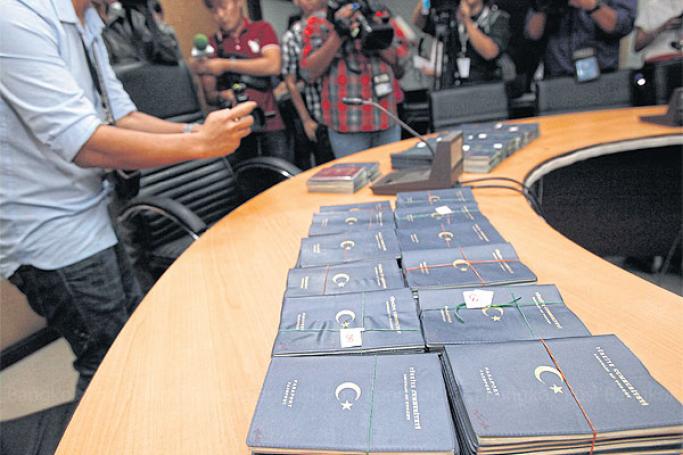

The money will usually cover the journey as well as a fake passport, which may be issued at the start of the trip in China or at other points along the way such as Bangkok or Kuala Lumpur.

Mr Surapong was unable to confirm whether some of the Uighurs use their Chinese passports to leave China. But his investigation found many do not use passports at all, instead preferring to exploit unguarded stretches of border or simply bribe officials.

A source who met more than 200 Uighur migrants at a Songkhla immigration detention centre in March last year said most had thrown away their Chinese passports before entering Thailand.

“It was particularly the case for Uighurs who hold Chinese passports, because they don’t want to be [identified as Chinese and] sent back to Xinjiang province,” the source said.

Mr Surapong said one thing is clear: The traffickers have been operating with relative impunity for many years, and in that time have built strong networks and developed close relationship with locals and corrupt officials. Because of this, they are able to easily evade targeted crackdowns and can exploit holes in Thailand’s border security.

“Most of them sneak through Thailand without going through immigration at the borders,” he said.

LEADING THE WAY

Traffickers usually use one of three main routes to smuggle Uighurs from Xinjiang, an autonomous region in China’s northwest, to Turkey.

One is to travel from Xinjiang by plane to Kunming, the capital of China’s Yunnan province which shares a border with Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam.

From Kunming, the smugglers take the Uighurs out by bus and continue their journey on land. They travel through the mountainous Xishuangbanna region, the southernmost part of Yunnan province, and cross the border into Laos. From there it’s a short overland journey to Thailand, crossing the border in Chiang Rai province.

Another route would see the Uighurs entering Myanmar from Kunming, and travelling to Thailand or Malaysia by boat, perhaps going via Koh Phra Thong.

The third overland route is through Vietnam. This usually involves a flight from Xinjiang to Ho Chi Minh City, from where the migrants will travel overland through Cambodia and across the Thai border at Aranyaprathet, in Sa Kaeo province.

Worasit Piriyawiboon, the lawyer who represented 17 Uighurs who were among a large group deported from Thailand earlier this year, said his clients entered Thailand from Cambodia in March last year.

“They came in through Sa Kaeo, a similar route to the one taken by suspects in the Erawan Shrine bombing,” the lawyer said.

Mr Worasit declined to comment on whether his clients had come through Thailand with the help of a smuggling ring.

However, he said, “My clients consisted of [four] adults and [13] children. Do you think they would be able to come to Thailand on their own?”

Mr Worasit said he had managed to get his clients sent to Turkey because they had been able to show Turkish passports verified by the government.

He did not represent the rest of migrants at that time because they did not have verified passports. In total, 173 of the Uighur group were later sent to Turkey, while another 109 were sent to China.

BUMPS IN THE ROAD

While most Uighurs arrive in and depart Thailand by land, some manage to pass through international airports.

Mr Surapong said Don Mueang airport was a popular entry point for Uighur migrants arriving on Chinese passports.

Whichever route they take to get to Thailand, once here the Uighurs will be taken by trafficking gangs to the South, usually Songkhla province, by bus or train.

From there they can cross the border to Malaysia, usually bypassing immigration.

Their destination is Kuala Lumpur, where they will board a flight to Turkey. The gangs usually like the Uighurs to fly out of Malaysia as they believe Muslim countries will be more sympathetic to their plight.

Mr Surapong said the Uighurs generally travelled in small numbers, compared to Rohingya migrant groups which can number up to 500.

But he said the Uighurs can still be subjected to the same extortion and harsh conditions encountered by the Rohingya.

“Once they get to Songkhla, the Uighurs will be detained at the same camps as the Rohingya, which is around Khao Mai Kaew,” Mr Surapong explained. “The smugglers usually ask for more money before they release them from the detention camps in the same way they did with the Rohingya.”

The discovery of several mass graves in remote jungle camps around that area earlier this year stands as testament to what happens to those who do not pay.

TIES TO TERROR

Regional terrorism expert Stephanie Kam from the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research in Singapore said the Uighur smuggling network also extended to Indonesia.

This included travelling by boat to Sumatra and flying from central and south Sulawesi, with the intention of travelling on to Turkey using fake Turkish passports.

In a report for the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, which Ms Kam’s centre is attached to, she warned of regional security ramifications if Thailand sent back the 109 Uighur men to China earlier this year. The report was published in July, before the Aug 17 Erawan Shrine attack.

Ms Kam’s report noted three Uighur men were recently sentenced to six years in prison for conspiring to meet the head of an Islamist Mujahidin Indonesia Timur (MIT) which has pledged allegiance to Isis.

“In the case of the recent [Erawan Shrine] attack, there is a possibility that some of the Uighurs may have had contact with Indonesian terrorists,” Ms Kam told Spectrum when asked about possible connections between criminal gangs and terror networks.

“Indonesia recently arrested a number of Uighurs who were found in training camps led by MIT in Central Sulawesi’s Poso.”

Ms Kam said there are an estimated 400-500 fighters of Chinese nationality fighting in Syria and Iraq.

She dismissed speculation that the Erawan bombers may have been connected to the right-wing Grey Wolves group in Turkey, saying it was more likely connected to the repatriation of the Uighur men and the disruption to lucrative smuggling networks.

“The attack to a symbolic site at the heart of the Thai capital was intended to cause a spectacle, and given the scale and lethality of attacks to foreigners and locals alike could not have been carried out by a local,” she said.

“The reasons for the attack most likely include existential grievances towards the Thai government, for reasons which include the recent decision to deport the Uighurs and Thailand’s crackdown on human smuggling. The policing of key smuggling routes into Thailand is likely to have angered members of the human smuggling networks.”

‘THIS ISSUE WILL ESCALATE’

Despite their years of experience, the smuggling gangs would be unable to operate without the complicity of corrupt officials. National police Chief Somyot Poompunmuang recently outlined six examples of misconduct by immigration officers which may help support human trafficking.

Pol Gen Somyot has vowed to clamp down on this corrupt behaviour. Yet Thailand’s reliance on tourism revenue means its borders will continue to remain open to foreigners who want to come in without having to go through a complicated visa process — and traffickers are able to exploit this vulnerability.

Mr Surapong said his team had found many foreign refugees in Thailand, and an equally large number of groups issuing fake passport for them.

While his team was investigating Uighur smuggling rings, they stumbled across an illegal Syrian passport operation in Bangkok.

“There are Bangladeshis who escape from poverty in their country and come to Thailand, there are Vietnamese defectors who run away from political turmoil in their country to hide in Thailand, there are Rohingya who escape from Myanmar to look for work, and there are also Chinese Uighurs who are suppressed by their government coming to Thailand,” Mr Surapong said.

“All of them are here to seek asylum and want to continue on to a third country. Thailand is basically a hub for these people to pass through.”

Because Thailand is not a party to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, migrants mostly need to keep a low profile while here and move on to a third country before claiming asylum.

Mr Surapong said the smuggling of Uighurs had risen in prominence only in the past three years, as a result of a surge in Rohingya trafficking groups building strong networks in Thailand. But the trade has become entrenched, and continues to draw more people.

“I want our government to take human trafficking and smuggling more seriously,” Mr Surapong said.

“The longer we wait, the more this trafficking issue will escalate. Syrian traffickers are starting to become the new problem, while the existing Rohingya and Uighur problems still haven’t been solved.”

http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/special-reports/699460/tied-up-in-a-traf...

You are viewing the old site.

Please update your bookmark to https://eng.mizzima.com.

Mizzima Weekly Magazine Issue...

14 December 2023

Spring Revolution Daily News f...

13 December 2023

New UK Burma sanctions welcome...

13 December 2023

Spring Revolution Daily News f...

12 December 2023

Spring Revolution Daily News f...

11 December 2023

Spring Revolution Daily News f...

08 December 2023

Spring Revolution Daily News f...

07 December 2023

Diaspora journalists increasin...

07 December 2023

School teachers to help at polling stations in Myeik