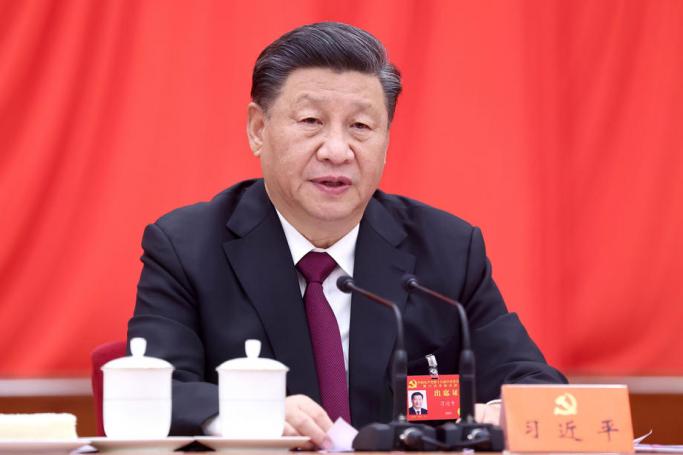

Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power in China matters to Myanmar. The Chinese president looks set to secure the green light for an unprecedented third term in office at the 20th National Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Beijing that begins tomorrow.

Under previous communist leaders China used to largely focus on developments on its own soil, yet under Xi the signs indicate China is looking for global dominance under a planned timeline leading up to 2050. The Chinese leader is stepping into Mao Tse-tung’s shoes and seeks to right the wrongs of British Colonial aggression against China.

The congress – a twice a decade meeting - comes as Xi faces political challenges, including deteriorating relations with the US and the Western world, as well as an ailing economy worsened by a strict Zero-Covid policy that has also fueled domestic discontent. That said, China has come a long way since the opening up after the death of leader Mao in 1976. But questions loom for Xi as to how much the state should guide the economy with Beijing’s emphasis at the moment on “common prosperity” – improving the lives of the man and woman on the street.

At the same time, speculation abounds that the Chinese leader is in the midst of a power struggle, not without its drama as a rumour circled last month of a potential coup against Xi, and a counter-rumour that has lingered for a while on whether he might have radical changes in store for the CCP.

Piece of the puzzle

So, where does Myanmar fit into the picture?

Few appear to fully understand the potential dangers China’s global plans pose for Myanmar, one of the key players currently in the process of being swallowed up by China, rendering it a “vassal state” – as one analyst put it - heavily dependent on its master.

Such a statement of possession may sound exaggerated but the analysts reading the tea leaves and with an ear to the CCP conclave are pointing to evolving CCP changes that could matter to Myanmar and its citizens – just one of many countries around the world who should be deeply concerned by Xi’s grand plans.

It has long been known that the CCP and other arms of the Chinese administration have expanded Chinese communist influence worldwide, not just with Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – and the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) - but also through agents infiltrating the West, and the cultural influence as seen in the Chinese cultural institutes that popped up – a more subtle variation on “The Thoughts of Chairman Mao Tse-Tung” books that flooded Western campuses in the 1960s during the 1966-76 Chinese Cultural Revolution.

Countries under the BRI such as Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Pakistan can be viewed as canaries in the coal mine when it comes to the potential dangers posed by the grand ambitions of Chairman Xi. But the dragon’s claws now reach as far as ports and transport arteries in Europe and Africa.

Desperate junta

Myanmar is just one of the countries being lured into the web. The country is particularly vulnerable to subversion and control by its northern neighbour due to the weakness of the Myanmar military

junta desperate for global friends, given the Western international pressure and sanctions and an angry Association of South East Asian Nations, annoyed at the diching of the Five-Point Consensus that was aimed at bringing peace to the land.

This year’s CCP congress matters to a range of countries under Beijing’s gaze.

Analysts such as The Diplomat’s Editor-in-Chief Shannon Tiezzi, indicate that a transformation of China is underway with this year’s CCP gathering. Despite the expected lengthy and turgid speeches, the congress will cement Xi’s position. As he recently put it: “China remains in an important period of strategic opportunity for development, but there are new changes in the opportunities and challenges the country faces.”

Names and terminology matter in this struggle for global dominance. As Tiezzi points out, the Chinese government is tweaking the message. As writer Andreea Brinza pointed out in The Diplomat, over the past year the term BRI has been quietly vanishing from official statements by Chinese leaders – especially Xi himself. As Brinza noted, however, “(T)he ideas around the BRI are not disappearing. Instead, they are mutating toward a new narrative: the Global Development Initiative (GDI).”

Bye Bye Uncle Sam

When it comes to world development, names should not be taken at face value. The GDI sounds benign. But this is the moniker under which Beijing - currently steering the world’s second-largest economy - wants to dominate the world to the extent that it kicks Uncle Sam off his pedestal and replaces him with the Dragon.

Analyst Brinza, writing in The Diplomat, says the ideas around the BRI are not disappearing. Instead, they are mutating toward the new narrative, the GDI. Launched during Xi Jinping’s speech at the UN General Assembly in September 2021, the GDI is as vague as the BRI used to be. It talks about promoting development in parallel with the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, by improving people’s lives, helping developing countries, driving innovation and being a link between people and nature. While the GDI aims to be a greener, high-quality focused, better BRI, in reality it is just another slogan that fits China’s needs and smacks of imposing global dominance.

As Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi recently said, the GDI and BRI are “twin engines” to enhance cooperation in traditional areas and foster new highlights. According to Wang, the GDI “will form synergy with other initiatives including the Belt and Road Initiative, Agenda 2063 of the African Union, and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development.”

Chinese ‘doublespeak’

Myanmar is particularly vulnerable at this juncture due in part to the crisis the generals have brought on their country in the wake of the February 2021 coup.

Part of the problem is that outsiders, whether the generals in Naypyitaw or politicians in the West, for that matter, do not pay enough attention to the “doublespeak” coming out of the halls in Beijing, nor do they fully understand how potentially invasive and destabilizing Beijing’s multi-strand programme of trade, communications and influence could be.

Beijing sells its programmes as “win-win” for China and the countries involved including Myanmar. But the tough reality is they make the recipient increasingly dependent on Beijing to an extent that few fathom, way beyond the concerns over debt traps, as voiced in bankrupt Sri Lanka and flooded Pakistan, amongst others.

Take LOGINK. Few have heard of the Chinese software programme that controls the flow of commodities and products under the BRI and now GDI framework. As BRI expert and analyst Andre Wheeler notes, LOGINK is being rolled out in Myanmar as part and parcel of the CMEC – essentially a trade and communications corridor that runs from China’s Yunnan Province across Myanmar to the Indian Ocean. In a nutshell, the use of LOGINK to manage trade and logistics across Myanmar means a major part of Myanmar’s trade and commodity data and the passage of goods falls into the hands of the Chinese Ministry of Transport. Instead of Naypyitaw maintaining sovereignty, independence and control, China will have undue insight and influence on a range of Myanmar trade and commodity issues, if the Myanmar generals buckle under and accept this high-tech infrastructure and software.

In simple terms, Beijing will have its fingers on the on-and-off switch of a significant proportion of Myanmar’s commerce and trade. The bigger picture could see Myanmar become heavily dependent on its northern neighbour, to the point where the CMEC corridor and a significant amount of trade and commerce falls under what could turn into an external economic zone of China that would stretch to the Indian Ocean.

Growing surveillance

Similarly, the Myanmar junta’s drive to turn the country into a surveillance state to combat opposition to its illegal rule could see Naypyitaw looking to Chinese companies for equipment and software that could allow Beijing undue influence in this sphere. Analysts point to the horrific surveillance and “social credit system” that China runs that controls the lives of Chinese citizens even to the point of blocking them from travel if their social credit score falls short, or they fail a Covid test.

The Myanmar junta could easily be lured into bringing in the types of controls on the internet that China uses. The generals have shown exasperation with the freedom afforded to Myanmar social media users, many of whom share anti-junta material on Facebook and in Telegram groups.

Similarly, the junta could be sold on other forms of controls that Beijing uses. Take the Zero-Covid policy of Xi that his government credits with keeping COVID-19 cases and deaths low in the crucible of the pandemic outbreak. While some analysts are optimistic Xi will use the CCP congress to ease his contentious Zero-Covid policy that has throttled growth and created a cascade of social and political problems, there is little evidence on the ground that this will be the case. China’s adherence to Zero-Covid has stunted growth, prompting economists to revise down their gross domestic growth forecasts for the economy.

A smartphone health application or health controls could be one more element of infrastructure that could be sold to the Myanmar generals in order for them to tighten their grip on the population. Chances are the data accumulated, while nominally under Myanmar control, would end up on Chinese servers.

All eyes on Xi

In terms of the process, Xi is expected to be named the party’s general secretary following the Congress this month, but he will not be confirmed for a third term as China’s head of state, or President, until an annual meeting of the rubber-stamp legislature in March 2023.

"China under Xi is moving in a totalitarian direction," Professor Steve Tsang of London University's School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) told the BBC. "China under Mao was a totalitarian system. We're not there yet, but we're moving in that direction."

Professor Tsang said the Congress could see changes to the party's constitution, with "Xi Jinping Thought" being further enshrined as the party's guiding philosophy.

"Xi Jinping Thought" is Xi's brand of Chinese socialism, an assertively nationalist philosophy which is highly sceptical of private business. Under his leadership the Chinese authorities have cracked down on major companies in several sectors of the economy.

"If that happens, they'll effectively make him a dictator," Professor Tsang told the BBC.

Given the virtual deification of China’s leader, there are questions as to whether Xi will seek to tighten his hold not only on the reins of China but also the influence and control he is developing overtly and covertly around the world.

Uncertainty for the Golden Land

Whatever happens, Myanmar needs to be wary of its northern neighbour. The Myanmar generals are grasping for the support of “friends” such as China and Russia as they struggle to remain in power.

The irony is that the Myanmar generals have long been wary of China and its influence over their country, yet their current weakness and need for economic and development support, mean their country faces serious danger from the country offering help.

Given how big the dragon has grown over a decade of stewardship under Xi, the Myanmar generals would be wise to heed the warning.

Reporting: Mizzima, The Diplomat, BBC